Overcoming a fear of heights provides a good example of how people can interrupt the vicious cycle of feelings, thoughts, physiological changes, behaviors, and relationships. Consider John Rogers, a 70 year old, successful and retired physician. He happened to fear heights and as a result, he also feared bridges. Other than the fear of heights, John was quite successful. He graduated from medical school and started a successful family practice. He was married for 45 years. And he had two grown children who were also successful.

Throughout most of his life, the fear of heights caused John little trouble, because he had been able to avoid much time near heights and tolerated his suffering as he occasionally crossed over bridges. However, once he retired, John wanted to travel. The more he traveled, the more he feared going over bridges. He hated the anxiety he experienced – the stomach twisting, the painful tension in his neck, the sweating, the racing heart. He feared that if he continued going over bridges, he would have a heart attack. And, he hated the words that raced through his head as he crossed a bridge – “I’m going to drive off the side. I’m going to drive over the side. I’m going to drive over the side….” He was afraid that he would listen to these words, turn the wheel, and drive through the rail. The rational part of John knew he would not have a heart attack. And, he knew he would not drive off the bridge. But as he approached bridges, the anxious thoughts over-powered his reason. He was nearly convinced that the problem could not be fixed.

When John was at a place he considered too high, he became anxious and expected to fall. His body became uncomfortably aroused, his heart sped up, he shook, his neck became taught and his stomach hurt. As he descended from the height, John experienced tremendous relief. The relief unfortunately taught him that leaving heights alleviates distress, so it is best to avoid heights. When he had to drive over bridges, he asked his wife to drive while he closed his eyes.

Inherent in this cycle is an underlying idea that experiencing distress is not acceptable. We believe that we should feel good. If we do not feel good, we believe something must be wrong.

Contrary to this widely held belief, humans are not designed to always feel good. As we go through our days, we experience myriad negative sensations including our stomach signaling hunger, our skin letting us know when we are hot or cold, and everything from our eyelids to our feet letting us know when we are tired. Anxiety also involves uncomfortable sensations – at times extremely uncomfortable. Anxiety serves a useful purpose. It prepares us to be more alert, more ready to react to problems that arise. For example, being at a great height can produce anxiety so that we are alert to where we should and should not walk.

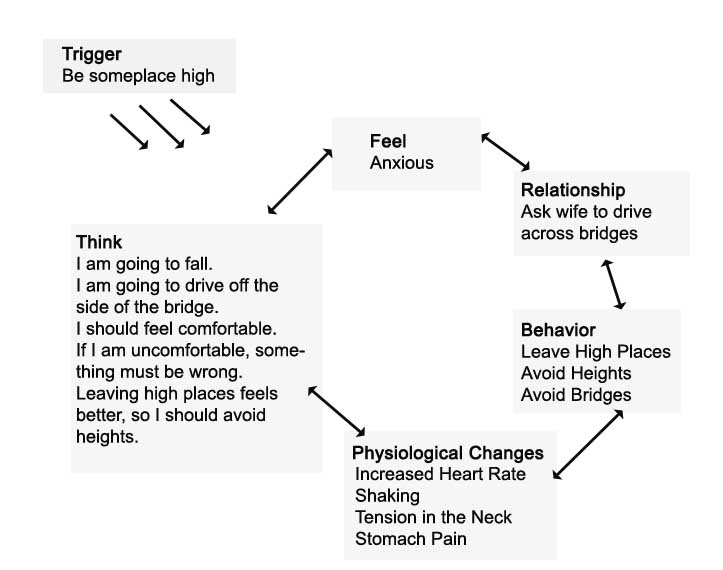

The cycle described above can be illustrated as follows:

Throughout most of his life, the fear of heights caused John little trouble, because he had been able to avoid much time near heights and tolerated his suffering as he occasionally crossed over bridges. However, once he retired, John wanted to travel. The more he traveled, the more he feared going over bridges. He hated the anxiety he experienced – the stomach twisting, the painful tension in his neck, the sweating, the racing heart. He feared that if he continued going over bridges, he would have a heart attack. And, he hated the words that raced through his head as he crossed a bridge – “I’m going to drive off the side. I’m going to drive over the side. I’m going to drive over the side….” He was afraid that he would listen to these words, turn the wheel, and drive through the rail. The rational part of John knew he would not have a heart attack. And, he knew he would not drive off the bridge. But as he approached bridges, the anxious thoughts over-powered his reason. He was nearly convinced that the problem could not be fixed.

When John was at a place he considered too high, he became anxious and expected to fall. His body became uncomfortably aroused, his heart sped up, he shook, his neck became taught and his stomach hurt. As he descended from the height, John experienced tremendous relief. The relief unfortunately taught him that leaving heights alleviates distress, so it is best to avoid heights. When he had to drive over bridges, he asked his wife to drive while he closed his eyes.

Inherent in this cycle is an underlying idea that experiencing distress is not acceptable. We believe that we should feel good. If we do not feel good, we believe something must be wrong.

Contrary to this widely held belief, humans are not designed to always feel good. As we go through our days, we experience myriad negative sensations including our stomach signaling hunger, our skin letting us know when we are hot or cold, and everything from our eyelids to our feet letting us know when we are tired. Anxiety also involves uncomfortable sensations – at times extremely uncomfortable. Anxiety serves a useful purpose. It prepares us to be more alert, more ready to react to problems that arise. For example, being at a great height can produce anxiety so that we are alert to where we should and should not walk.

The cycle described above can be illustrated as follows:

When people are asked what they think someone else should do to get over a fear of heights, ninety percent of people respond, “They should stand someplace really high and stay there until they are not afraid.” Most people intuit that if we face our fears, the fears will pass. To make the exposure to a fear useful, it must be repeated frequently until the brain accepts the idea that the situation is safe, falling off a height (or driving off a bridge) is quite improbable, and the anxious sensations are temporary. Thus for John to overcome his fear, he would need to go to heights until he became willing to experience the uncomfortable sensations of anxiety and until he recognized that he was safe at high places.

Most people can accept this idea, but not everyone has the courage to act on it. John accepted the idea in theory, and had the courage to gradually encounter increasing heights. He started by imagining himself driving over high bridges. Simply closing his eyes and creating an image of driving over a bridge was sufficient to arouse John’s anxiety. John initially fought the sensations of anxiety. He tried to make the sensations stop, but they continued to escalate as he imagined the drive.

Over time he learned to allow the anxiety to rise and run its course. In particular, he learned to accept the very real experiences of his heart rate increasing, his stomach hurting, his neck becoming tight, and his body shaking. He simultaneously learned not to focus on the anxious thoughts about driving off of bridges. As he accepted the anxious physical sensations, he found that the anxiety did not rise so high and it passed more quickly.

John imagined himself driving over high bridges until he was no longer bothered by the anxiety in these imaginary trips. He then stood on bridges, and approached the edges to look over. And finally he actually drove over low bridges, medium sized bridges, and eventually high bridges. He learned not to fight the anxiety he experienced during these encounters; and when he stopped fearing the anxiety it stopped escalating. The anxious sensations continued to occur, but they did not escalate because John did not fear them. He stopped challenging his fear of heights when it stopped interfering with his travels.

Most people can accept this idea, but not everyone has the courage to act on it. John accepted the idea in theory, and had the courage to gradually encounter increasing heights. He started by imagining himself driving over high bridges. Simply closing his eyes and creating an image of driving over a bridge was sufficient to arouse John’s anxiety. John initially fought the sensations of anxiety. He tried to make the sensations stop, but they continued to escalate as he imagined the drive.

Over time he learned to allow the anxiety to rise and run its course. In particular, he learned to accept the very real experiences of his heart rate increasing, his stomach hurting, his neck becoming tight, and his body shaking. He simultaneously learned not to focus on the anxious thoughts about driving off of bridges. As he accepted the anxious physical sensations, he found that the anxiety did not rise so high and it passed more quickly.

John imagined himself driving over high bridges until he was no longer bothered by the anxiety in these imaginary trips. He then stood on bridges, and approached the edges to look over. And finally he actually drove over low bridges, medium sized bridges, and eventually high bridges. He learned not to fight the anxiety he experienced during these encounters; and when he stopped fearing the anxiety it stopped escalating. The anxious sensations continued to occur, but they did not escalate because John did not fear them. He stopped challenging his fear of heights when it stopped interfering with his travels.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed